Lee and Low Books, March 2021

Reviews

Kirkus Reviews, ⭐️ starred review

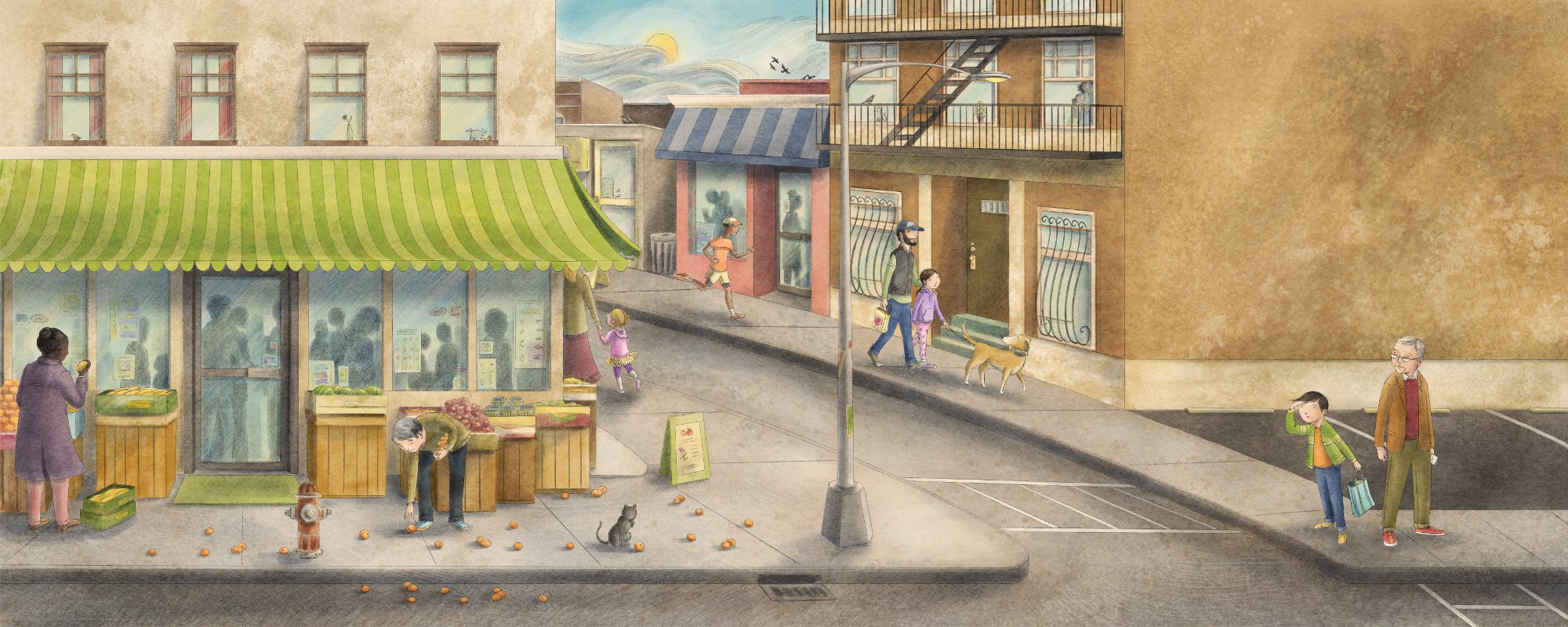

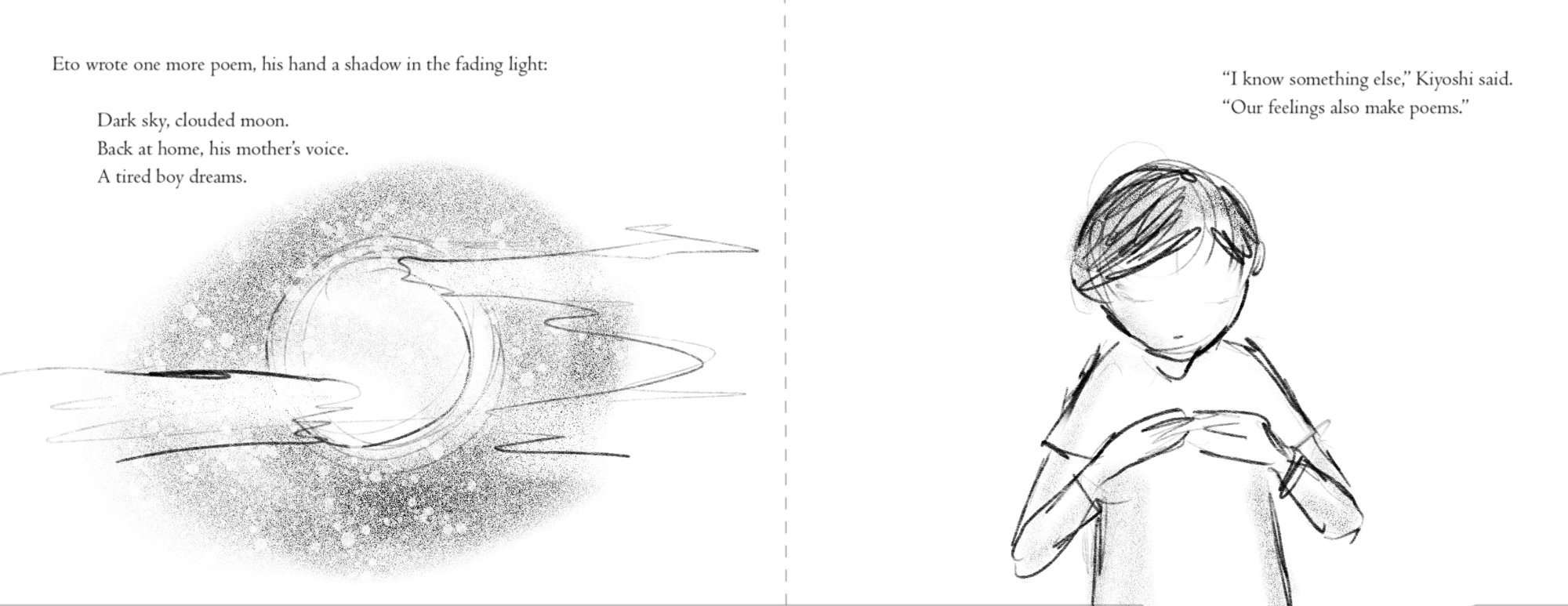

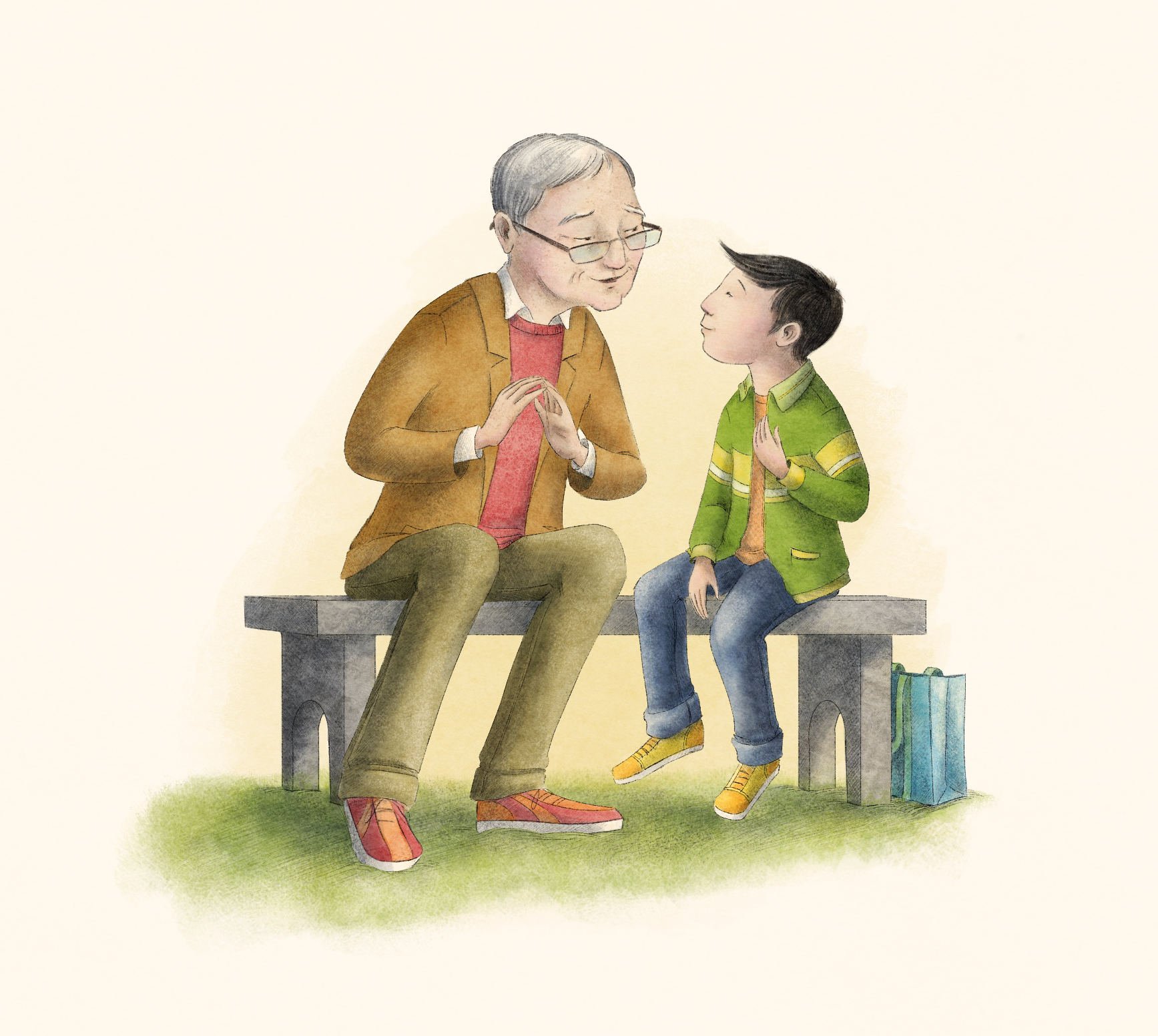

A neighborhood walk unleashes the power of poetry. Kiyoshi, a boy of Japanese heritage, watches his poet grandfather, Eto, write a poem in calligraphy. Intrigued, Kiyoshi asks, “Where do poems come from?” So begins a meditative walk through their bustling neighborhood, in which Kiyoshi discovers how to use his senses, his power of observation, and his imagination to build a poem. After each scene, Eto jots down a quick poem that serves as both a creative activity and an instruction for Kiyoshi. Eventually Kiyoshi discovers his own poetic voice, and together the boy and his grandfather find poems all around them. Spare, precise prose is coupled with the haiku Kiyoshi and his grandfather create, building the story through each new scene to expand Kiyoshi’s understanding of the origin of poems. Sensory language, such as flicked, whooshed, peeked, and reeled, not only builds readers’ vocabulary, but also models the vitality and precision of creative writing. The illustrations are just as thoughtfully crafted. Precisely rendered, the artwork is soft, warm, and captivating, offering vastly different perspectives and diverse characters who make up an apparently North American neighborhood that feels both familiar and new for a boy discovering how to view the world the way a poet does. Earth tones, coupled with bright yellows, pinks, and greens, draw readers in and encourage them to linger over each spread. An author’s note provides additional information about haiku. See, hear, touch, taste, smell...and imagine poetry all around you.

School Library Journal, ⭐️ starred review

Kiyoshi wishes he could write haiku like Eto, his grandfather. When Kiyoshi asks him “Where do poems come from?” Eto responds by putting paper and a pen in his pocket and taking Kiyoshi for a walk. As they traverse the city all the way to the river, Eto writes poems based on what they see and hear including tumbling oranges, the flap of wings, an abandoned teddybear, and the ending of a day. Meanwhile, Kiyoshi puzzles out how to find a poem. At the river Eto asks Kiyoshi if now he understands where poems come from. Kiyoshi has been paying attention: “‘They come from here,’ he said, and opened his arms wide to take in the river and the sky and the distant buildings. ‘And they come from here,’ he said, and pointed to his own heart.” The text does an excellent job of showing the process, as it unfolds, without overexplaining or complicating the narrative. Wonderful digital illustrations complement and expand on the text, combining clean lines, realistic details, and a variety of perspectives, from bird’s-eye views to close-ups. Warm, inviting colors with pops of bright pink on the flowering trees (cherry blossoms, perhaps) provide quiet clues to location, while the people in a multicultural cityscape have a variety of skin tones and an attitude of friendliness. An age appropriate author’s note further explains the art of haiku. VERDICT A beautiful book on making art out of observations. Whether employed to invite children and adults into writing or as a nurturing read-aloud, this is recommended for all collections.

The Horn Book

Kiyoshi appreciates the haiku written by his grandfather, the “wise poet” Eto, and asks him, “Where do poems come from?” In response, his grandfather pockets a pen and paper and takes him on a walk through their busy urban neighborhood. Passing by a fruit stand, Kiyoshi pats a cat standing on a pyramid of oranges. After the page-turn, the fruit is scattered on the ground, and Eto writes a poem: “Hill of orange suns. / Cat leaps. Oranges tumble. / The cat licks his paw.” They continue their walk, and Kiyoshi’s senses are heightened as he notices a flower in a sidewalk crack and the passing “whoosh” of a girl on a bike. Pigeons fly overhead, leading to Eto’s next haiku; a forgotten teddy bear behind a construction wall leads to the third. Like Karlins’s text, Wong’s digital illustrations are delicate and precise. She uses soft pastels along with grays and browns, employing a variety of perspectives to capture the beauty of a North American cityscape. By the end of the walk Kiyoshi is inspired to create his own poem, having learned that poetry comes from the world around him and from the feelings in his heart, “the way they come together.” An author’s note explains the Japanese origins of haiku and how it differs from the American form. This warm, loving picture book might just inspire a poetry walk.

Publishers Weekly

White-haired grandfather Eto, a “wise poet,” sits at a table writing a haiku with a brush. When Kiyoshi asks him where poems come from, Eto suggests a walk. At the corner store, the sun shines while a cat knocks over a pyramid of oranges. Eto writes: “Hill of orange suns./ Cat leaps. Oranges tumble./ The cat licks his paw.” Kiyoshi’s still puzzled: “Does that mean poems come from seeing things?” But Eto doesn’t reply; instead, the two continue their journey, Eto writing haiku about experiences they have and feelings elicited. Digitally created illustrations by Wong (I’ll Be the Water) portray grandfather and grandson in careful detail and give plenty of visual information about the town they walk through and the riverside park where they sit and talk. At last, Kiyoshi writes a haiku of his own. Each poem brings Kiyoshi closer to the insight that poetry combines sensory perception and emotion—and closer to his grandfather, too. Karlins’s (Starring Lorenzo and Einstein, Too) explanation is clear and accessible, and provides a fine springboard for discussion. An author’s note further describes haiku.

Booklist

Where does poetry come from? That’s what Kiyoshi, a little boy, is trying to find out in this picture book from author and poet Karlins. In order to help Kiyoshi, Kiyoshi’s grandfather, also a poet, takes him on a perambulation through their city. Inspired by sights, sounds, smells, and feelings along the way, the grandfather periodically grabs his pen and notebook and transforms everyday experiences into haiku. That includes observing oranges stacked high at the grocery store, listening to the whir of pigeons’ wings, and feeling lonely by the river at sunset. In the end, Kiyoshi tries his own hand at writing and, on the way home, sees many more possibilities for poetry. By writing to all the senses, Karlins places readers right alongside Kiyoshi on his walk.Wong’s illustrations bring them in even deeper, progressing from simple portraits of the home to streets of city neighborhoods to stunning nighttime scenes by an illuminated river. The caring relationship between grandfather and grandson is the glue that holds the story together.

Junior Library Guild

Junior Library Guild Gold Standard Selection